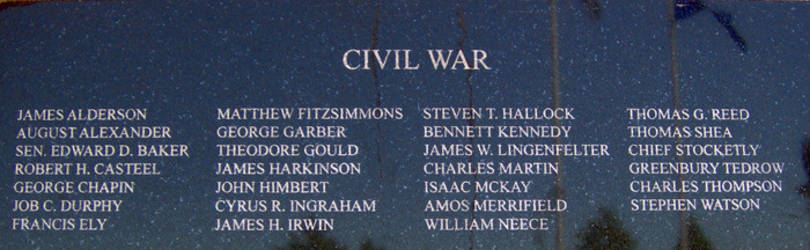

Francis Ely

Representing: Union

Unit History

- 1st Oregon Cavalry A

Family History

Created by Brian

Francis Ely

- Birth

- 1840

Ireland

- Death

- 11 Mar 1864 (aged 23–24)

Walla Walla County, Washington, USA

- Burial

- Walla Walla, Walla Walla County, Washington, USA

- Memorial ID

- 17589775

- Private, Company A, 1st Oregon Cavalry. Enlisted November 21, 1861 and was executed by firing squad for desertion. He was the only Oregon soldier executed during the Civil War. Read the story here http://www.osbar.org/publications/bulletin/04augsep/heritage.html

The exact location of the grave is unknown but executed prisoners were usually buried at or near the site of execution. -

Oregon Legal HeritageMILITARY JUSTICE

Law and order, Oregon and the Civil War

By Scott McArthurAmerica is at war. The newspapers and TV news programs tell of military justice. Military justice played an important part in early Oregon history, including the only military execution of the war on the Pacific Coast.

There was an active military presence in the Oregon Country during the Civil War. Troops in Oregon, Washington Territory and what later would become Idaho Territory reported to the Military District of Oregon headed by Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord at Fort Vancouver.

Although there was no active Confederate activity in Oregon during the Civil War, the Army did have repeated run-ins with the Indian bands east of the Cascades. Mostly, soldiers in the Oregon Country fought boredom, poor pay, bad food, disease and often-indifferent leadership.

Military justice during the Civil War was long on military and, by today’s standards, short on justice.

Minor offenses by soldiers were handled within the units. Those who were drunk, absent without leave or otherwise derelict were punished with up to 30 days in the guard house, time in the stocks, bucking and gagging, close order drill while carrying a knapsack of sand, or hard labor while tethered to a ball and chain.

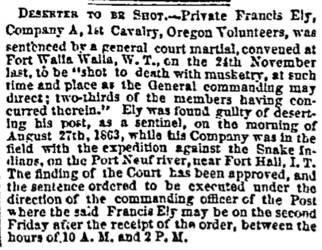

The most serious offense was desertion. That was a general court martial offense.

Desertion was common. Gold had been discovered in Eastern Oregon, in Idaho and in the Fraser River Valley of British Columbia. A good hand could find work in the mines paying $5 a day. The private soldier was paid $13 a month. Payday was six times a year.

At the start of the war, the maximum penalty for desertion from Western units was:

"Fifty lashes on the bare back, well laid on with a raw hide; to be indelibly marked on the left hip with the letter "D" an inch and a half long, and to be drummed out of the Service."

Flogging was abolished in August 1861.

George A. Wilson, who deserted from his Oregon unit at Fort Walla Walla, was sentenced:

"To be confined at hard labor in charge of the guard for six months, with a ball and chain attached to his left leg, the ball weighing at least 12 pounds . . . "

Another deserter from the same company had his head shaved.

A few were set to work building the fortifications at Fort Cape Disappointment (later Fort Canby) at the north entrance to the Columbia River. Civilian labor was hard to find.

All told 149 men deserted during the war from Oregon’s two bob-tailed Infantry and Cavalry regiments.

Some were repeat deserters. Patriotic citizens and eager legislatures and county governments provided cash bonuses for those who would enlist. Those who enlisted in the Oregon units got both state and local bonuses for signing up. That was a powerful reason to enlist, accept the bonus, desert and enlist somewhere else again. In March 1865 President Abraham Lincoln granted amnesty to all Union Army deserters. All they had to do to clear their record was to return to an Army post and surrender.

Captain William Kelly, commander at Fort Klamath in southern Oregon, wrote his superiors at Fort Vancouver in May 1865. He had, he said, a deserter who had turned himself in and who had admitted to enlisting, collecting his bonus and then deserting from four units in California and Nevada Territory. He confessed that he may have enlisted more than that, but things were a bit hazy because he drank a lot.

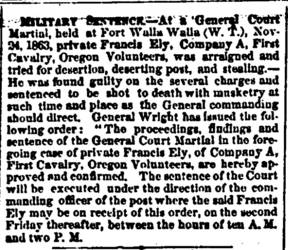

The greatest penalty for desertion during the Civil War was death by firing squad. Only one man suffered that penalty in the Oregon Country.

That was Private Frances Ely, a 21-year-old native of Ireland, who enlisted in Captain Thomas S. (Smiley) Harris’ Company A, 1st Oregon Volunteer Cavalry at Jacksonville in the winter of 1861.

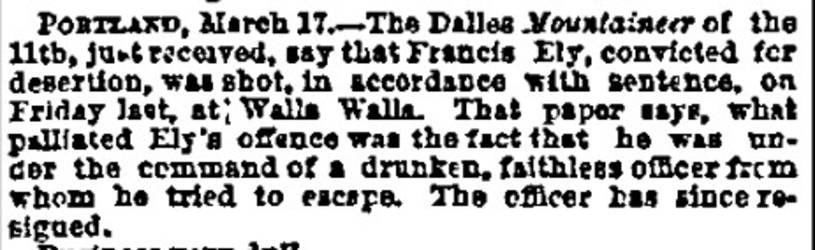

Harris was a lousy officer. He was forced to resign after he backed down and allowed himself to be pistol-whipped by a drunken civilian while in uniform on leave in Idaho.

Ely deserted his post at Fort Boise in July 1863, just as his company was preparing to leave to do battle with Chief Pocatello in Southern Idaho. He took his government horse with him. Ely was found on the road to the gold mines and was taken to Fort Walla Walla where he was tried by court martial and sentenced to death.

In at least nine previous instances, General George Wright, commander of the Department of the Pacific, had reduced the death sentence for desertion to life in prison.

Harris’ successor as company commander was Captain (later Major) William V. Rinehart who years later wrote:

"For three days before the fatal Friday (Ely was executed March 11, 1864) no passes were allowed even to visit the town only a mile away. Check roll-call of every company was held after midnight each night when the Captain and 1st Sergeant quietly stole from bunk to bunk checking off the names to see that every man was in his bed.

"Believing in a respite or possibly a reprieve, Col. Maury at Fort Dalles had ordered men from Company B there and Company A at Walla Walla, to be distributed about 10 miles apart along the road from Fort Dalles to Walla Walla . . . to serve the looked-for order from Gen. Wright at San Francisco."

The order never came.

"As the hour of 2:00 o’clock p.m. approached, the battalion of four Companies followed by the firing parties and the cart in which sat Ely on his rough board coffin and riding backward, with a file of guards walking on either side of the cart, proceeded to the corral which was surrounded by a high board fence. . . . After Adjt. Kapus had read the order for his execution, the black cap was drawn down over his eyes and one volley sent four balls through his heart. His body was carted away from the fatigue party and buried without the honors of war."

Military justice applied to civil employees of the Army as well. Tom Hughes, a civilian interpreter at Fort Walla Walla, got drunk and shot his government issue horse. His officer put him to work, still hung over, in the broiling sun, made him dig a hole to bury the horse, and then banned him from the fort.

Indians who murdered were turned over to the civilian courts. Reservation Indians who got drunk, stole or fled the reservation without permission were imprisoned in the guardhouse, flogged with a whip or beaten with a hoe handle. The worst punishment for an Indian was to have his (or her) head shaved.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Scott McArthur, Monmouth arbitrator and mediator, is a former member of the Board of Governors and is a frequent contributor to the Bulletin. This article is an excerpt from his yet-unpublished book on the Civil War in the Pacific Northwest.© 2004 Scott McArthur

Cemetery

Buried at Fort Walla Walla Military Cemetery